What’s In a Roll (or, not all Jelly Rolls are equivalent)

I’ve been using 2.5″ strips a bit lately—commonly called Jelly Roll strips. But, my recent purchases haven’t been fabrics by Moda, so I’ve quickly learned that not all rolls are equal. Here’s a breakdown of commonly available rolls and the number of strips included.

What is a Jelly Roll?

A Jelly Roll (which is a term specifically for Moda rolls, but is commonly used to describe all strip pre-cuts) is a pre-cut fabric assortment of strips measuring 2.5″×Width of Fabric (~40–44″). They typically contain at least one strip from every print and colorway in a fabric collection, and sometimes contain duplicate prints to reach a specific strip count.

How many strips are in a Jelly Roll?

The number of strips in a roll varies by manufacturer, and sometimes even within a manufacturer’s offerings.

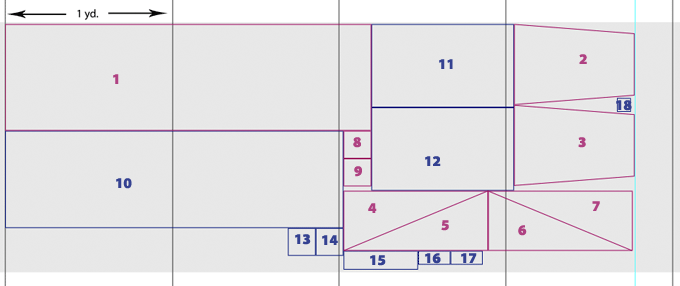

| Strip Count | Manufacturer and Name |

|---|---|

| † count is dependent on number of prints in collection | |

| * Riley Blake Designs has a few Rolie Polies made of blenders that come with as few as 11 strips, and at least one solids Rolie Polie with 45. Free Spirit sometimes has 36 strips in their Designer Rolls for larger collections (and possibly other numbers). Kauffman has Solid Roll Ups that often come with 40 or 41 strips and batik sets with as few as 28. | |

| 11–28† | Connecting Threads Sample Strips |

| 20 | Joann Fabrics Fabric Palette/Central Jellie |

| 20 | Moda Junior Jelly Roll |

| 21–28*† | Riley Blake Designs Rolie Polie |

| 28-45* | Robert Kauffman Roll Up |

| 30* | Free Spirit/Westminster Designer Roll |

| 40 | Hoffman Fabrics Bali Pop |

| 40 | Moda Jelly Roll |

| 40 | Northcott Stone Strips |

| 40 | Timeless Treasures Tonga Treat |

Strip count in a roll sometimes varies, even in the ones I didn’t mark with an asterisk, so always check the description of what you buy online or look for a number in store (or count, if you have to).

There’s also the rare occasion that a strip is cut incorrectly and not caught by quality control (I have had this happen multiple times with Moda charm packs, less often with rolls), so when picking patterns to make with your precuts or planning out your own, try to build in a small margin of unused strips. And, make sure to count your strips before starting the project!

Where To Buy

You can find these all in various online fabric shops and it seems like more and more local shops also carry them. Depending on what fabric brands a shop carries, you may not be able to find every type in a single location.

Prices also vary. You’re typically going to pay slightly more per equivalent yard (40 strips is just over 2.75 yards), and while the price generally relates to number of strips, that’s not always true. And, of course, manufacturers charge different amounts per yard (and have differing qualities of fabric), so the different roll prices will reflect that.

Watch out for store-made rolls!

Not that they are inherently bad, but be on the look out for store-made rolls as opposed to official releases by the fabric companies. These rolls may have a different amount of strips, fewer prints or more duplicates, be cut in half the width of fabric instead of full, have strips larger or smaller than 2.5″ tall, or any number of other variations (yes, I’ve purchased one with all of those attributes).

Official rolls typically have printed tags and are bound by ribbon printed with the manufacturer’s name or come shrink wrapped.

Know what you’re buying, ask questions if things aren’t clear, and be happy sewing!

If you think I’ve missed any strip collections, please let me know in the comments.

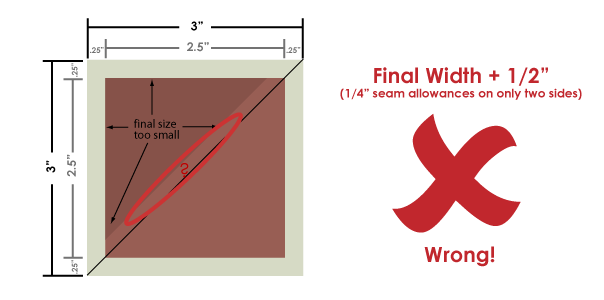

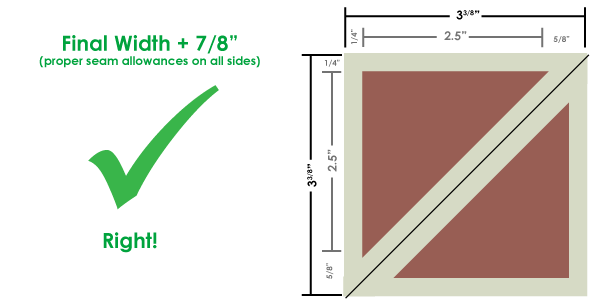

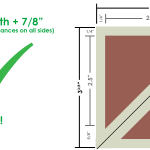

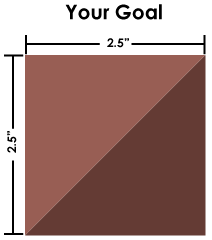

Math’s no fun, at least in my opinion. So, as I get into this whole quilting thing, I’ve been doing more math than I like, and doing it poorly. I have found that Adobe Illustrator is great to play around and piece my quilt blocks together in a digital sense, but unlike quilt-specific software (like Electric Quilt), it doesn’t magically add my seam allowances for cutting out the bits and pieces. My most annoying mistake: sizing half-square triangles.

Math’s no fun, at least in my opinion. So, as I get into this whole quilting thing, I’ve been doing more math than I like, and doing it poorly. I have found that Adobe Illustrator is great to play around and piece my quilt blocks together in a digital sense, but unlike quilt-specific software (like Electric Quilt), it doesn’t magically add my seam allowances for cutting out the bits and pieces. My most annoying mistake: sizing half-square triangles.